It is said Shakespeare wrote "King Lear" when quarantined during the plague. Thoreau wrote "Walden" when he self-quarantined himself to simply experience solitude. It's been two weeks since "Shelter in place" began in California for the Coronavirus and yet it has been so hard for me to put pen to paper so to speak. My neighborhood is eerily quiet and the freeway noise has died down. Birdsong is loud and clear. Inside the house we've each colonized a space as our "work area" and during school/office hours we sport our headsets and are glued to our screens. The saving grace is we have all our meals together, play at least a boardgame together and go for a walk in the dark, you guessed it, together.

I know I am privileged as I am able to work remotely and am getting a paycheck and most people I know are healthy. The economy is tanking but I have a shock absorber that will hopefully take me and my family through, something that countless others cannot count on. However, privileged as I am, I cannot help being caught up in fleeting moments of nostalgia and feeling sorry for ourselves - when can we go on a proper hike, when can I go to The Getty, will I ever be able to travel? But these moments pass and I try to take a look at the positive. What Greta Thurnberg struggled to achieve, the coronavirus has temporarily achieved - cleaner air and a respite for Earth from human pollution. Spring is here and there are birds nesting in my backyard. Signs of bird-life everywhere even if everything else is looking dead. Despite being closeted together 24 X 7 we've managed to not get on each other's nerves too much. Since I am not driving it has given me back some valuable time which I have spent reading and visiting art museums online.

I wrapped up Mantel's masterpiece "The Mirror and the Light" last week. I wouldn't be surprised if this one also wins her the Booker for the third time! There are so many things to say about the book but the plague and sweating sickness which feature only in a minor role in this book seemed prescient. Her characters deal with the plague as a fact of life and are ruled by a selfish, fickle king. The trilogy is a perfect companion for these times.

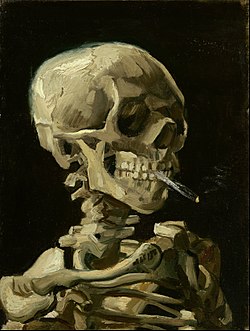

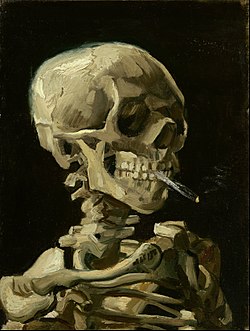

This week I spent a lot of time visiting the Van Gogh Museum online. I was lucky enough to have been there in person two years back. I remembered the "Skeleton smoking a cigar"

I don't know how well known this painting was, but it was new to me at that time. And then I found out that Tamino's song "Cigar" was inspired by this painting. Tamino's concert was the first casualty for me due to the Coronavirus. I had tickets to go see him on March 11th in LA and we decided to cancel in the interest of social distancing.

More than the sunflowers and the irises I remember being struck by Van Gogh's paintings of trees - where he focused not on the top but on the bottom - the roots of trees. I am reading "Underland" by Robert McFarlane and hence I seem more tuned to looking at the understorey

This was one of my favorite Van Gogh paintings. One of my friends went on a forest walk in India a few weeks back and wrote a poignant piece on what the forest meant to him. He talks about the need to slow down to nature's pace to become resilient. Maybe it is just that my brain is looking to make sense of these quarantines and social distancing, but his words seemed to resonate as we've all slowed down these past few weeks and there is no doubt that we have given the Earth a chance to heal. But will we able to heal and recover from this? Only time will tell.

Let me close this random rambling post with a self portrait of the man

The bandaged ear recalls what happened after 60+ days of spending time with Gauguin (only partly kidding). As we are all closeted with our near and dear ones - a friendly reminder to take care of boundaries, not to push each other's buttons and to pay attention to our mental health in unprecedented times like these.

I know I am privileged as I am able to work remotely and am getting a paycheck and most people I know are healthy. The economy is tanking but I have a shock absorber that will hopefully take me and my family through, something that countless others cannot count on. However, privileged as I am, I cannot help being caught up in fleeting moments of nostalgia and feeling sorry for ourselves - when can we go on a proper hike, when can I go to The Getty, will I ever be able to travel? But these moments pass and I try to take a look at the positive. What Greta Thurnberg struggled to achieve, the coronavirus has temporarily achieved - cleaner air and a respite for Earth from human pollution. Spring is here and there are birds nesting in my backyard. Signs of bird-life everywhere even if everything else is looking dead. Despite being closeted together 24 X 7 we've managed to not get on each other's nerves too much. Since I am not driving it has given me back some valuable time which I have spent reading and visiting art museums online.

I wrapped up Mantel's masterpiece "The Mirror and the Light" last week. I wouldn't be surprised if this one also wins her the Booker for the third time! There are so many things to say about the book but the plague and sweating sickness which feature only in a minor role in this book seemed prescient. Her characters deal with the plague as a fact of life and are ruled by a selfish, fickle king. The trilogy is a perfect companion for these times.

This week I spent a lot of time visiting the Van Gogh Museum online. I was lucky enough to have been there in person two years back. I remembered the "Skeleton smoking a cigar"

I don't know how well known this painting was, but it was new to me at that time. And then I found out that Tamino's song "Cigar" was inspired by this painting. Tamino's concert was the first casualty for me due to the Coronavirus. I had tickets to go see him on March 11th in LA and we decided to cancel in the interest of social distancing.

More than the sunflowers and the irises I remember being struck by Van Gogh's paintings of trees - where he focused not on the top but on the bottom - the roots of trees. I am reading "Underland" by Robert McFarlane and hence I seem more tuned to looking at the understorey

This was one of my favorite Van Gogh paintings. One of my friends went on a forest walk in India a few weeks back and wrote a poignant piece on what the forest meant to him. He talks about the need to slow down to nature's pace to become resilient. Maybe it is just that my brain is looking to make sense of these quarantines and social distancing, but his words seemed to resonate as we've all slowed down these past few weeks and there is no doubt that we have given the Earth a chance to heal. But will we able to heal and recover from this? Only time will tell.

Let me close this random rambling post with a self portrait of the man

The bandaged ear recalls what happened after 60+ days of spending time with Gauguin (only partly kidding). As we are all closeted with our near and dear ones - a friendly reminder to take care of boundaries, not to push each other's buttons and to pay attention to our mental health in unprecedented times like these.